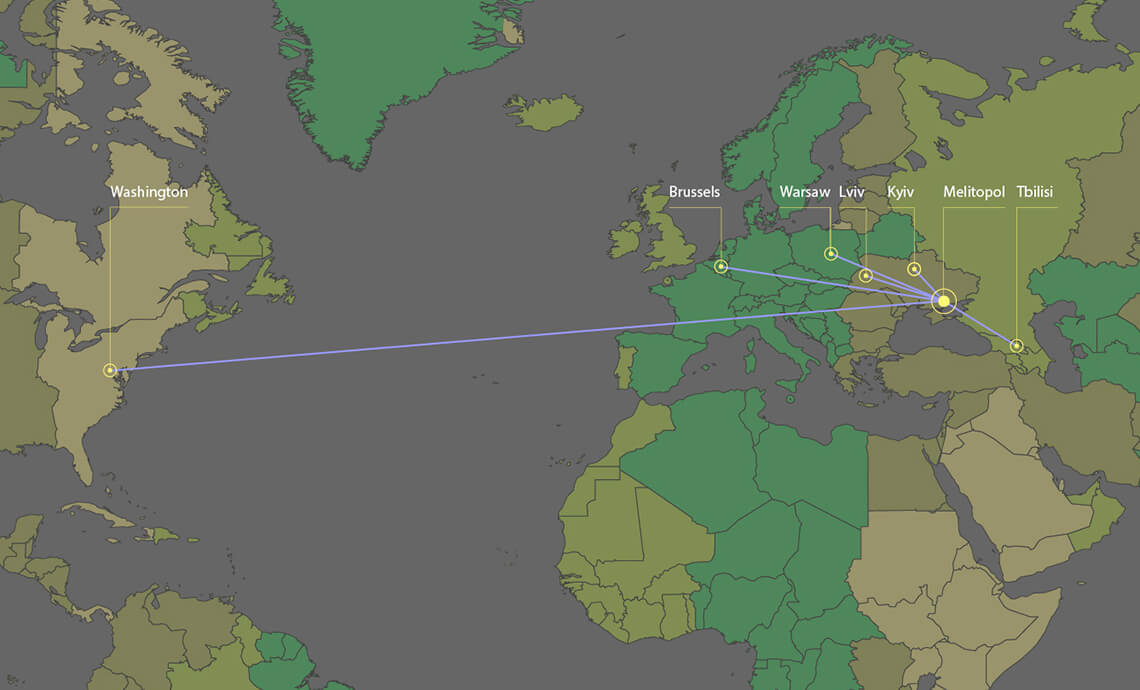

The political situation in Ukraine has thus far prevented me from getting to Kiev to conduct my research in person. Consequently, I am trying to introduce myself to the scene there by doing my interviews remotely, through Skype. So far, the only artists I have been able to get in touch with are Yulia Kostereva and Yuriy Kruchak, who share an artistic practice; they are also co-founder and founder of Open Place, a platform dedicated to, according to their website, the “development of creative research” and the “establishment of the connections between an art process and different layers of the Ukrainian society.”

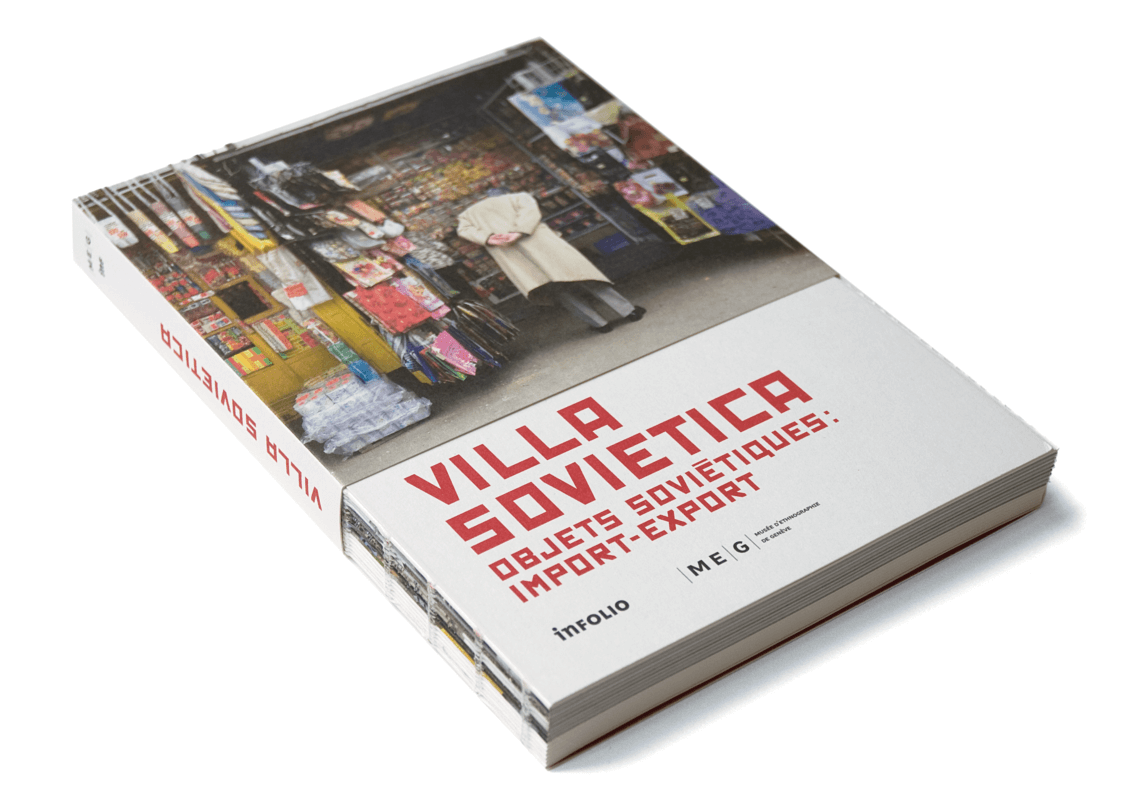

I spoke with Yulia about Open Place. I was intrigued by the interactive and collaborative nature of their work, and the manner in which they involve the surrounding community in dealing with local issues. One of the pieces that struck me, looking at their website, was The 7th of November (the date of the 1917 October Revolution), an art intervention that they staged in Geneva in 2009. What intrigued me about it was their use of the plaid plastic bags that are a familiar accessory not only in Eastern Europe, but also the West, used by refugees and migrants. The artists invited 20 people, citizens of Geneva, to move 80 of these bags, filled with newspapers, across the city, and eventually bring them to a public sculpture in front of the Palace of Nations, Broken Chair, which was installed as a monument in support of the international treaty for a ban on cluster bombs. The participants of the action used the bags to “repair” the chair, acting as an artificial support or fourth leg.

The purpose of the action was to bring attention to the status of migrants in Geneva, and in general. The artist recalls that as artists from Eastern Europe in Switzerland, they themselves felt like “barbarians,” which they imagine is not dissimilar to the way in which most immigrants there feel, or are made to feel by the inhabitants. The bags were used because of their iconic association with foreigners. Indeed, in their travels through the city, they made quite a sight, as 80 of these large bags blocked the view of the city on the bus, and disrupted sightseeing, interfering with the pristine view. By bringing these bags out into the public space, they confronted passersby with a reality that they might not like to see or acknowledge. They brought the bags to the chair to repair it, using it as a symbol of a “broken nation” or union. They also wanted to show that “barbarians” could also fix something.

In doing this action, they occupied public space and showed that this is not just a space for tourism, but also a space for dialogue. They also gave the local citizens who participated the experience of what it might be like to exist as a foreigner in that environment. Yulia told me that the people who participated seemed to really make this connection after the performance, and one woman went as far as to say that she “felt like Christ,” after participating in it.

A similar collaborative effort can be seen in Subbotnik, where the participants came together to do gardening work – often a task associated with the Soviet-era subbotnik, or mandatory work party. During the Soviet era, subbotniks would involve picking potatoes at harvest time, or cleaning up a factory or school. In Yulia and Yuriy’s Subbotnik, the participants planted a garden, according to the artists’ instructions. In the end, the result was a small flower garden that formed a portrait of Lenin, the inventor of subbotniks. The artists liked the idea of the work party, stating that “when you earn money [for your work] there is a difference between the people who earn more or less money; if you work for free, you are equal.” The artists chose this activity because of the connection with local traditions, mainly citing the large flower clock in the center of Geneva, which people care for on a regular basis.

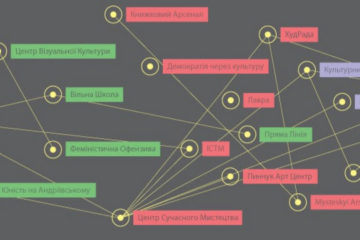

Aside from these projects in Switzerland, which were done in the context of a residency that the artists had there, with their Open Place platform, Yulia and Yuriy are both committed to promoting contemporary art in Ukraine. They mentioned that they wanted to create an alternative to the Pinchuk Art Center, which doesn’t always necessarily deal with the reality of contemporary Ukraine. Rather, they wanted to create a more “flexible structure, that can change and be implemented in many places, everywhere.” They also wanted to ensure that contemporary art was connected with the general public, not just the regular art-going crowd, thus they deliberately located their space outside of the city center. Performative and participatory artforms do not have a strong tradition in Ukraine, and when I asked Yulia where their ideas came from, she told me about an artistic exchange that she and Yuriy participated in in Kharkiv in 1998. She spoke about the freedom that they were given to work on their project, and the collaborative spirit of the exchange, which hosted participants from Kharkiv and Nuremberg. After this, they realized not only the importance of being able to have direct contact with their viewers, but also the importance of feedback and dialogue. Ironically, Yulia told me that she and Yuriy used to lament the fact that people in Ukraine weren’t active – meaning prior to the events of 2013-2014. She said that as artists, they didn’t want to simply make “critical art,” which only shows the problem and doesn’t propose anything new. Rather, she spoke about the empowering nature of people coming together to solve a problem. Simply lamenting the problem “makes people feel helpless,” she said, but if they “feel free and educated, then they can solve it…” Later, she stated that “when people aren’t free, they feel poor, not active, this makes them feel worse.” So their artistic practice starts from the idea of empowering people to come together to find a solution.

The artists have worked with blind people and differently abled people, to create a more inclusive environment for them, in a society where they are otherwise marginalized. [It is rather symptomatic of post-Soviet spaces that differently abled people are denied access to public spaces, rather than being integrated into daily life.] For example, they have created a work of art that blind people can interact with. Before they could do this, however, they had to establish trust within he community, so they created new maps of the city to replace the old, Soviet era maps that the rehabilitation centers in Kiev were using, and made maps that corresponded to the new situation in the city. Then, they worked with volunteers to walk the people around the city using these maps, so that they could become familiar with the layout. Initially, they made smaller sculptures that one could hold in one’s hand, and touch. Later, they made a hands-on sculpture to give sighted people the experience of what it is like to be blind. In this piece, they created a grid, and depending on which square of the grid the person stood on, different sounds would emanate – the sound of a barking dog, for example – that would indicate that one needed to move to another square.

The Open Place platform is a great initiative that combines art and activism, and works with the local community, to bring artists and laypeople together to solve problems through interaction, and artistic activity. I look forward to the day when I can visit their space in person.